PART I

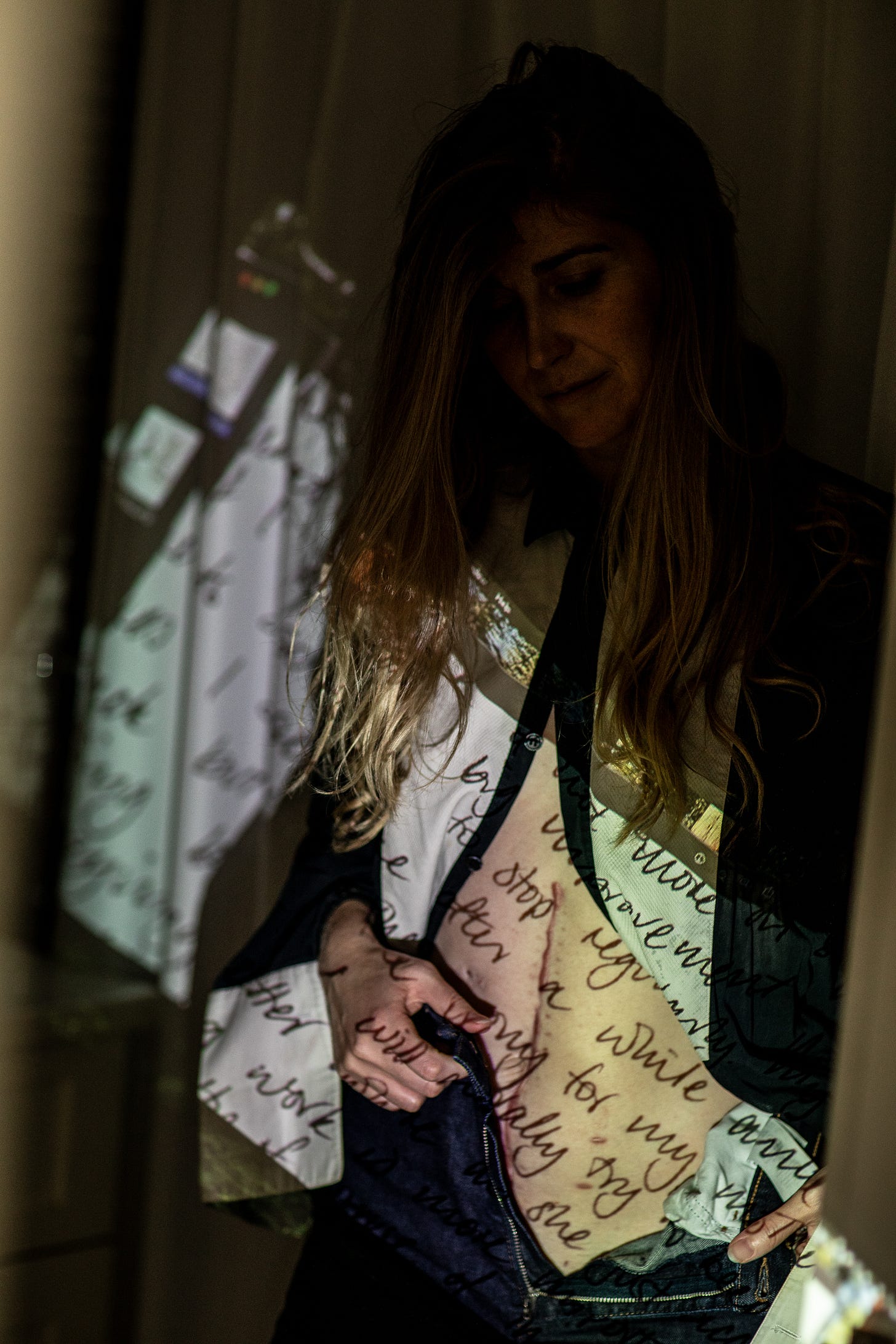

What if the moment you thought you were growing life inside you, your body was quietly fighting to stay alive itself? by Billie Whitehouse

As the co-creator of Cycle Interrupted, the goal of this Substack is to share stories about womanhood and the medical system. About our cycles, interrupted; the beautiful, and painful, dualities of life; and the challenges and adversity that we face. With this in mind, I am so humbled and grateful to share the words of a friend below.

I’m not sure where I first met Billie. I believe it was as young teenagers in Australia. We are the same age, and likely grew up within walking distance to each other. Billie was always bright, bubbly, with a confidence I admired. Billie moved to NYC, and I watched her become a brilliant founder, futures thinker and passionate voice for all she believes in. When I heard through mutual friends that she had gone through her own medical insanity, I reached out. In quiet Instagram DMs, we shared mutual outrage. Beneath her warm smile and a life of wandering was also the reality that existence can be truly brutal. Thank you, Billie, for sharing the below. You are a force and I have nothing but respect for you.

Xx Katrina

This is not a story for the faint of heart. And by no means is it written for sympathy; in fact, the opposite. I don’t think any cancer patient wants your sympathy. Maybe they want your understanding, but that is a difficult ask.

For me, I want to share this in case someone else is having similar symptoms: pain, change in digestion, change in stool, vomiting, rashes and, eventually, blood in the stool — if you are having these signs, insist that the doctors do a colonoscopy or scan ASAP. Get your blood checked, and don’t let anyone tell you what's going on with your body if you know something is wrong.

I had to learn the hard way about truly listening to my body. Losing a child when you are 22 weeks pregnant and so ready for a family has been earth shattering. Having a cancer diagnosis on top of that forces you to change. Because cancer inevitably changes everything: how you live, how you spend your time, who you spend time with, how you value your time, your body, and even your small hope for fertility.

June 1st was National Cancer Survivor Day, and this is dedicated to anyone who is going through these changes that life forces upon us.

I’d had a strange tummy for many years, but even more so after coming off an IUD. Some friends had told me it took them 6 months for their digestion to go back to normal, so I assumed the changes were hormonal. But after 3 months of pain, I went to a gastrointestinal doctor to understand if this was to be expected. He told me it was gas, but I had never had gas that felt like this before.

During the pandemic, I had fallen in love with an Aussie Peter Pan in New York. Like many, he and I like to travel and work remotely. This particular year, a month after removing my IUD, we were in the Dominican Republic, and experienced our first hurricane in more ways than one. After yet another night of being sick and thinking I had an amoeba parasite, I went to a local doctor who asked if I was pregnant. Not knowing the answer, I took a pregnancy test and found out I was 8 weeks along.

When we found out, there was some hesitation — mine because of the professional partnerships I was currently working on, and wondering what the time off would do for my career; for him, hesitation around the changes to his life that he loved so much. After much deliberation, we decided that we would keep the baby.

The local gastroenterologist did not want to perform any additional tests with this news, but ordered a stool test. The results were shared with both local doctors and a gastroenterologist in NYC, but with no follow-up. I had an ever-growing pain under my right rib and — with humor being our survival mechanism — we nicknamed this pain “Gavin.” Once I found out I was pregnant, every doctor said that the pain, strange bowel movements, and vomiting were simply pregnancy-related.

Through December of that year, my partner and I met with more doctors, and continued to travel, which often affected my digestion. By January the following year, Gavin was getting extreme. I was unable to stop vomiting, and Gavin was making my belly swollen and disfigured. I went to an OBGYN who sent me home with the explanation that I must have a bug.

Ten days later, I went back to the hospital. I had not been able to hold down food for two weeks. At 19 weeks pregnant, I went to the maternity ward. I wanted to make sure that if I had gastritis — which every doctor had told me I had — that it wasn’t impacting the baby. They sent me home, saying I would feel better in a few days. I hate hospitals and will avoid them at all costs, but my worry for my baby superseded any concern I had for myself.

Another week later, unable to stop vomiting or move from a fetal position in the bathroom. I had not been to the bathroom in almost two and a half weeks at this point. The doctor’s persistent advice was to take MiraLax, even after I had told them I had been taking it for months with little success.

With my symptoms dismissed by every doctor I had seen for the last 6 months, I finally insisted we return to the hospital. The doctors, once again, didn’t listen. In tears, I screamed at them: “NO ONE IS LISTENING TO ME. PLEASE STOP BEING SO CONDESCENDING.” I was tired of managing medical professionals who were clearly avoiding the signs that I was unwell, and instead, chasing some idea of what is “normal.” It was my first time experiencing firsthand that doctors are not taught to truly listen to their patients, but taught to follow procedure — which often feels disconnected from anything human.

At 10pm that night, they ordered a CT scan and found a 8 cm tumour in my right transverse colon, positioned exactly where I felt Gavin. The next day, they ordered emergency surgery.

The first doctor that came in, whom I now call “Dr Death,” kept telling me that I was going to die (not the kind of energy you want to bring into the operating room). I then met with my surgeon who said this was a routine operation, far more normal than heart operations, and that they would take out the tumor, test it for cancer, and the baby should be okay. He indicated that there was a high likelihood of cancer from the beginning, but wasn’t sentencing me to death, which felt like a huge step forward.

That Friday afternoon, my partner was making jokes to my nurses as they wheeled me into the operating room. I am so grateful he was able to make me laugh at this point: “Just be warned: We are from the Southern Hemisphere, so her bowels run in the opposite direction.” He stayed with me every night, sleeping in a cot with his vintage French trench coat over him as a blanket. And when they said that we could terminate the pregnancy if we needed to, his face showed me how much he wanted to keep this baby.

The operating room had boxes from floor to ceiling, and didn’t feel like the sterile environment I had expected. I woke to hearing the 2nd-in-charge doctor saying he needed to run out the door so he could get the train for his President’s Day weekend getaway. I lay there, in discomfort, hoping someone would tell me how the operation had gone. The post-op room was loud, without real doors or any sort of privacy, and I had tubes in many of my orifices.

After 2 days in the makeshift post-op room, I was moved to the heart attack floor, as there was nowhere for me anywhere else. Here, I would have regular visits from the fertility teams to check on the baby. All seemed to be doing well: There was a heartbeat, and I was able to keep down fluids and some small bites of food.

On the seventh day of post-op recovery, there was no longer a heartbeat. I think the night before, I must have known, as I cried hysterically all night. They checked with 3 different machines and confirmed he was gone.

That night, they prepped me to have my miscarriage procedure. They wanted to implement the contraction devices at midnight, but I asked if they would do it at 8pm so that I could sleep. What I didn’t know was that meant I would have to give birth to a tiny little blue baby in the bathroom of my hospital room because they did not come around early enough to knock me out.

I have never cried so much in my life. It’s like floodgates; it just doesn’t stop, even years later. Losing a child is hard enough. Adding a cancer diagnosis, a massive project I was working on being disbanded, and my bank going bust — all in the first three months of that year — makes me believe the universe must have wanted me to change.

After my surgery and diagnosis of colon cancer (bowel cancer for any Australian reader), that year was devoted to change. Fertility preservation, chemo, and an ostomy reversal were followed by some celebration of life, or a “chemo-moon” — the travel that we had so desperately missed. My scans remained clear that year, and we were able to take a trip to see our families in Australia. But it wasn’t the end of my story — Part II will be shared soon.

This is a hard story to share, but I believe that someone else could be experiencing similar symptoms and may advocate for themselves differently if they read this. You don’t have to always learn something from horrific experiences; sometimes it can just be awful and you are allowed to feel awful. I am finally able to see some of these learnings but this is an ongoing lesson for me. I have a different perspective on what's important and the joy that is life. A few of those lessons:

Listening to your body has to be your number one priority.

A new understanding of how broken our systems are when it comes to women’s health.

Gratitude for the people who do show up. I am so grateful for my partner who has been my absolute rock throughout this experience

Cancer teaches you the kind of resilience you don’t ask for but are forced to grow into

Grief doesn’t always show up how you expect it to — but it’s there, and it deserves to be honored

Your identity isn’t tied to what you lose. It’s shaped by how you carry it forward

And a deep, humbling truth: Not everyone gets to have children. And that is a kind of grief that lives in the quiet corners of every day.

To anyone navigating illness, loss, or fertility challenges: You are not alone. It’s okay to be angry. It’s okay to grieve. It’s okay to laugh at the absurdity of it all. And it’s okay to talk about the things we’re told to quietly endure.

For more ways to support colon cancer research:

beautifully written, absolutely tragic. from one survivor to another, no story is the same and i will always hold space for you and your story!